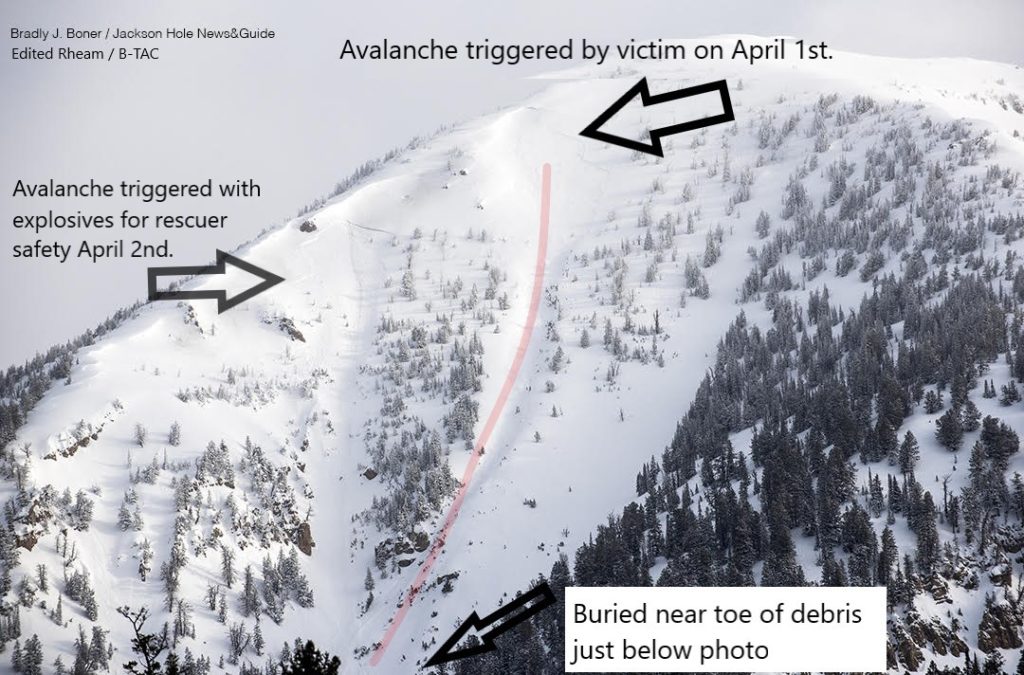

Five days ago, a skier was caught and killed by an avalanche outside of Silverthorne, CO. Twelve days prior a snowmobiler was buried and killed in an avalanche near Jackson, WY, and two days before that another skier was buried and killed, also near Jackson, WY. Two of the three victims were not wearing a transceiver, and all three incidents occurred in wind loaded avalanche paths beneath corniced ridgelines.

This brief summary of events, while not unordinary for this time of year, unveils a bone-chilling truth not only to backcountry snowsports enthusiasts but to all outdoor recreationists alike: in pursuit of the fulfillment and gratification we seek from our mountain environments, we are always walking a line between risk and consequence—the probability of an accident and the magnitude of said accident, respectively. If the line becomes too narrow, one false step can lead to tragedy.

The width of this line is our margin for error. Low risk paired with low consequence gives us a wide margin. If we ski through a low-angle meadow with no exposure to avalanche terrain, we can ski all over the slope, stop for lunch, drink beers, make snow angels, and we’ll never suffer the consequences of being caught in an avalanche because the risk of triggering an avalanche is nil. We are operating within a wide margin for error. Our margin narrows as we begin to introduce factors that increase either risk or consequence. If our slope exceeds 30 degrees, we are introducing risk for snow to move downhill under its own weight. If we have a poorly supported slab in the snowpack, the risk that this snow will move when agitated increases. We may accept this risk if the consequence is low, e.g. we may choose to ski over a small, steep knoll with unstable snow if the terrain is low-consequence. Conversely, we may choose to expose ourselves to high-consequence terrain, skiing above cliffs or in a large slide path, if we know that the risk of an avalanche is low. The margin of error is our lifeline, and the narrower it becomes, the less we can depend upon it.

We know this already, don’t we? If we weren’t aware of the inherent risks and consequences of outdoor activities, why would we ski with avalanche safety gear, climb with ropes, and boat with life jackets? Here we must examine an age-old theme of the human psyche: the relationship between knowledge and critical thinking.

Neuro/psych heads be warned, I have a lay-man’s understanding of these terms and I am prepared to smile and nod at any criticism towards my elementary theory of mind. But that’s the point I’m trying to make: we don’t all need a degree in brain sciences to understand that knowing something and actually thinking critically about it are two different things. We know that an avalanche transceiver will help us locate an avalanche victim. But do we understand that this piece of equipment is to be used in an emergency situation and that we should plan to avoid ever using it outside of practice scenarios? Furthermore, do we understand how to prevent ourselves from ever needing to use it, or how our sympathetic nerves will respond if we do need to use it?

This is not to say that critical thinking supersedes knowledge, but rather that knowledge provides a vehicle that critical thinking can drive, that critical thinking without knowledge leaves you walking down a busy freeway wondering if you’re going to be hit by a semi-truck, and that knowledge without critical thinking is like a car without a driver—convenient in theory but probably not actually attainable. As a thought exercise, imagine putting Immanuel Kant and a copy of the SWAG at the top of Teton Pass. Each will get buried in an avalanche unless they interact with one another, despite the Critique of Pure Reason’s applicability towards analyzing heuristic traps.

So how did we arrive here, visualizing Kant reading the SWAG aside Wyoming Hwy. 22 and making informed decisions about skiing in avalanche terrain? The current episode of global pandemic has caused us to question the acceptability of participating in outdoor activities. Some of us are frustrated that our favorite trailheads have been closed to facilitate social distancing and prevent accidents that could require medical care. Others are angry that stubborn enthusiasts are ignoring stay-at-home orders and choosing to recreate outside despite condemnation. I am not writing to tell you whether or not you are allowed to go skiing or climbing this spring. Instead, I am proposing that the global pandemic should be factored into the framework of knowing your margin for error and thinking critically about it.

With this mindset, we can, and must, address the influence of the pandemic on our recreation pragmatically. The pandemic narrows our margin for error from the perspectives of both risk and consequence. Firstly, in addition to the inherent risks of outdoor activities, we must address the newly introduced risk of spreading COVID-19. We may feel disgruntled over restricted access or cancellation of travel plans, but ultimately, we must take the initiative to limit contact with other people to a bare minimum. Management of this risk will look different among outdoor communities. Take, for example, Seattle, a metropolitan area of four million people, with droves of enthusiasts cramming their way into crowded trailheads on any given Saturday, versus Bozeman, with a population of only 50,000, where one can essentially walk out his or her backdoor and hike for miles without seeing another human. We must accept the circumstances of our environment, and manage the risk of disease spreading accordingly.

Secondly, the pandemic’s increased burden on our healthcare system further increases the consequence of an accident. If we become injured, we are diverting resources from patients in need, and inversely, threatening ourselves due to suppression of resources. We are also exposing ourselves to the consequence of contracting and spreading COVID-19 from unnecessary interaction with medical personnel. Although we find solace in the meditative effects of outdoor recreation, we must selflessly consider this increased consequence for the time being.

Thirdly, we are faced with the unusual conundrum of filling our extra free time with engaging and fulfilling activities, lest we succumb to the mental prison of boredom. We will all take a different approach to fulfilling ourselves, but undeniably, some of us are getting out more than we usually do (guilty as charged). If we increase the frequency of our recreation, we are increasing the iterations for the probability of our risks to take effect. If I go climbing three times this week, I have a greater chance of being hit by rockfall than if I were to only go once, regardless of the probability of rockfall. Due to increased frequency, especially in conjunction with the risk of disease spreading and the consequence of a stressed healthcare system, we must deliberately widen our margin for error when planning our outdoor activities.

This list is neither comprehensive nor absolute. These are the most prominent factors that I am considering when planning my outdoor activities this spring, and I am curious to hear others’ perspectives. The bottom line is: consider the pandemic as an additional influence on your assessment of margin for error. Know the risks and consequences associated with the pandemic, and think critically about them. Augment your decision making in outdoor activities with your awareness of the pandemic’s impact. Wear a transceiver when you’re skiing in the backcountry, and don’t ski in wind loaded avalanche paths. It’s not just you and your loved ones who will be impacted by tragedy this time.

Use this spring as an opportunity for self-improvement. Find a big hill and time how long it takes you to run up it. Go back tomorrow for a faster time. Stretch or do yoga every day. Experiment with nutrition and find what works best for you. Build a sleeping platform in the back of your SUV so that when this all blows over, maybe this summer or maybe this fall, you’ll wake up at the base of the crag and approach the rock like Michelangelo’s David, chiseled in body and spirit, feeling as if you are made from this very rock, ready to throw your sling at routes you’ve only dreamed of.

chiseled in body and spirit lesssgooooo